How can it be that there is no Hall of Fame for dogs…

There is a Pinball Hall of Fame, a Mascot Hall of Fame, a Hot Dog Hall of Fame. There is a Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame. There is a Robot Hall of Fame. There is a Burlesque Hall of Fame. There are an estimated 3,000 halls of fame. And no Hall of Fame for dogs. Now quilters are honored, polka dancers are honored, tow truck drivers are honored, stickball players are honored, toys are honored, kites are honored…but not our best friends. Until now.

So let’s get started and meet the inductees into the World Dog Hall of Fame…Seaman...frontier explorer, Barry...mountain rescuer, Greyfriars Bobby...loyal dog, Sallie Ann Jarrett...war dog, Old Drum...hunting dog, Bob...railway dog, Nipper...spokesdog, Owney...postal dog, Jean...movie actor, Warren Remedy...show dog, Togo...sled dog, Stubby...war dog, Strongheart...movie actor, Rags...war dog, Rin Tin Tin...movie actor,Hachiko...loyal dog, Mick the Miller...dog racer, Buddy...guide dog, Patsy Ann...town dog, Shep...loyal dog, Skippy...movie actor, Terry/Toto...movie actor, Sinbad...war dog, Brownie...town dog, Chips...war dog, Fala...Presidential dog, Pal...movie actor, Bing...war dog, Smoky...war dog, King Buck...field dog, Laika...space dog, Higgins...movie actor, Count & Dingo...space dogs, Westy Whizzer...dog racer, Ashley Whippet...sport dog, Ballyregan Bob...dog racer, Endal...service dog, Uggie...movie actor, Chaser...smart dog…

Available in Hardcover, Paperback, or Kindle versions

Seaman...frontier explorer

In the summer of 1803, as he was rounding up supplies for the first-ever organized American crossing of the North American continent, Meriwether Lewis bought a dog. He paid $20 - half of his monthly captain’s wage. He wrote in his journal, “The dog was of the newfoundland breed one that I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey.” Lewis named his dog Seaman.

The big black dog would make the entire trip to the Pacific Ocean and back with the Corps of Discovery, serving as sentry, hunter, and companion. Early in the trip Captain Lewis recorded in his journal, “I made my dog take as many [squirrels] each day as I had occasion for. They were fat and I thought them when fried a pleasant food. Many of these squirrels were black. They swim very light on the water and make pretty good speed. My dog would take the squirrels in the water, kill them, and swimming bring them in his mouth to the boat.”

Seaman earned his keep as a game retriever and watchdog. He had more than a few adventures on the trail as well. He was stolen once by Clatsop Indians and on another occasion was badly bitten by a beaver, nearing dying from blood loss. Seaman also performed an occasional rescue of a Corpsmen trapped in the Missouri River.

The end of Seaman’s story is unknown but it is assumed the big dog made it back across the continent with the Corps of Discovery since Lewis would certainly have mentioned it in his journal had he not. A dog collar has been discovered with an inscription that reads: “The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific Ocean through the interior of the continent of North America.”

Barry...mountain rescuer

Not many dogs have an entire breed named after them. Before Barry his breed was known as an Alpine Mastiff or maybe an Alpine Spaniel. For many decades after his death in 1814, however, the dogs were called “Barry hounds.” Finally, in 1880 the breed was officially recognized by the Swiss Kennel Club and named for its place of origin: the St Bernard.

The Great St Bernard Pass is the third highest road passage in the Swiss Alps at 8,100 feet. Hard by the border of Italy the passage has been a heavily travelled route for centuries. The Great St Bernard Hospice has operated in the pass for 1,000 years and in that time has made at least that many rescues in the mountains. They began breeding large dogs to aid in the work at least by the 1700s.

The pass is completely snow-free only a couple of months each year. Big dogs could handle big snow drifts and help pack down the snow for the two-legged rescuers. They could also provide critical warmth to injured travelers trapped in snow with their bodies and thick fur. Of all the St Bernard dog rescuers working the pass down through time none was more famous than Barry.

Barry began his work in the monastery in 1800 and was credited with saving 40 people before retiring in 1812. His legend has swelled through the years but the story most often relayed about his skill was the retrieval of a small boy from an ice cavern. Barry warmed the shivering child with his tongue and then maneuvered him onto his back for a ride back to the hospice.

Barry was not the size of modern St Bernards but he was burly enough to get the job done. Ironically, today’s dogs are too big to participate in mountain rescues since they are too heavy to life up and down from a helicopter with a guide. The last recorded rescue by a St Bernard was in 1955. Their biggest value now is in hospital and nursing home visits where they are loved for their gentle disposition and patience.

Barry’s rescue days ended when a monk brought him off the mountain to live his retirement days in the Swiss capital of Bern. After his death, Barry’s skin was preserved and he was put on display in the Natural History Museum of Bern. His presence thrilled a local professor, Friedrich Meisner, who wrote in 1816, “I find it pleasant and also comforting to think that this faithful dog, who saved the lives of so many people, will not be quickly forgotten after his death!”

Barry was certainly not forgotten. Through the years the exploits of all rescue dogs in the Alps have come to land on Barry’s resume. He has starred in countless children’s books and is honored with a monument at the entrance of the Cimetière des Chiens in Paris. The Great St Bernard Hospice still breeds the fabled dogs and for the past 200 years one of the dogs has always been named Barry.

Barry is still regarded as an ambassador for Switzerland around the world. “It’s like chocolate and cheese,” mused Michale Keller, vice director of Bern Tourism, about the fame of Swiss exports. “I’d say Barry’s in about third position.” Even ahead of Swiss watches and Swiss army knives.

Greyfriars Bobby...loyal dog

A gardener by trade, John Gray couldn’t find a job in his field after moving to Edinburgh in 1850. Instead, he took a job as a night watchman. To combat the loneliness of his patrols Gray adopted a little Skye terrier he named Bobby. The harsh night winds blowing off the North Sea took its toll on the constable and he contracted tuberculosis; he passed away on February 15, 1858.

After he was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard the townsfolk noticed that Bobby was not leaving his master’s grave. He would not leave for 14 years. The groundskeeper built a small shelter for Bobby beside the grave. When the one o’clock gun in town was shot off to signal lunch Bobby would leave and go to the Traill Coffee House - always a favorite of Gray - and he would be given a meal.

The devoted Bobby naturally became an Edinburgh favorite. When a law was passed in 1867 that all dogs in town must be licensed the Lord Provost paid for the levy and a collar. Bobby remained a faithful guardian of the grave until his death in 1872.

By that time Bobby’s story had spread far beyond Edinburgh. Angelia Georgina Burdett-Coutts, considered the richest heiress in England and the president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, commissioned a life-size bronze statue of Greyfriars Bobby just before he died. The esteemed William Brodie, one of Britain’s busiest bust portraiture artists, executed the depiction of Bobby. In a long career filled with dozens of distinguished works the bronze of the loyal Skye terrier is probably Brodie’s most famous work.

The memorial fountain was placed at the foot of the George IV bridge. Over the years it became a custom to rub Bobby’s nose for luck, wearing it down to the metal. The city tried to keep it blackened but eventually gave up. The statue was only the first of the tributes to the “world’s most faithful dog.” There have paintings, photographs, films, and biographies.

A dog’s fealty to a master’s grave was something of a trope in the 19th century. Even Seaman, about whom nothing is known for certainty beyond what was written in Meriwether Lewis’s journal, was said to have a note left with his collar that read, “after Lewis died in 1809 no gentle means could draw him from the spot of interment. He refused to take every kind of food which was offered him and actually pined away and died with grief upon his master’s grave.”

Stories of such canine devotion don’t play as well in more cynical modern times. Bobby’s reputation as the standard of loyalty has spawned plenty of doubters, including one theory that there were actually two Bobbys who lived in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Regardless, the fame of Greyfriars Bobby endures and the words that adorn his headstone remain as true today as they did 150 years ago: “Greyfriars Bobby – died 14th January 1872 – aged 16 years – Let his loyalty and devotion be a lesson to us all.”

Sallie Ann Jarrett...war dog

Dogs have followed men into war as long as there have been dogs and war. Often their greatest value is doing what dogs do best - being a companion in the long, tedious times between battles.

Sallie Ann Jarrett joined the Civil War effort with the Eleventh Pennsylvania Infantry in 1861. She arrived in a basket in West Chester as the unit prepared to fill the Union lines. The bull terrier was only four weeks old and the regiment immediately adopted her as their mascot. The brindle pup was named for the two things that dominated the troops’ minds the most in training camp - their commander Colonel Phaon Jarrett and Sallie Ann, a local girl who would stop by camp with biscuits and a pretty smile.

Sallie Ann was doted on but she also learned the code of the soldier. She was described in journals as “cleanly in her habits and strictly honest, never touching the rations of men unless given to her. She would lie down by haversacks full of meat, or stand by while fresh beef was being issued and never touch it.” Sallie Ann recognized bugle calls and when the men were called to formation she always assumed her position along her namesake at the head of the regiment.

The Eleventh Pennsylvania shipped south and saw its first action at the Battle of Cedar Mountain in August 1862. Sallie remained calm, licking the wounds of fallen men and even picking at bullets that struck the ground around their position. In the ferocious fighting at Antietam the regiment tried to keep Sallie out of range but she would not leave the men. She picked up singed fur from a Confederate bullet for her stubbornness. It turned out Sallie had gone under fire in the family way - a month later she gave birth to a litter of ten pups.

Sallie Ann became renowned for her ability to recognize the individual members of her regiment in the fog of war. She always found her way back to the Eleventh Pennsylvania. When the regiment was undergoing review by the commander-in-chief, Abe Lincoln paused when he reached the handsome dog and doffed his stovepipe hat in acknowledgement. That’s how the regimental history remembers it, anyway.

In July 1863 Sallie Ann Jarrett was back on her home turf in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania defending against Confederate invasion. Her position was overtaken but she refused to abandon the fallen men around her. She was not relieved for three days when a member of the Eleventh Pennsylvania arrived back on the scene to find a tired and hungry mascot.

In May 1864 a rebel minie ball penetrated Sallie’s neck. The wound was not deemed mortal so the bullet was left to work its way out and Sallie continued to stay with her regiment. Nine months later, with the Union Army making its final assault against Confederate positions in northern Virginia an enemy bullet pierced Sallie Ann’s brain. She was buried in the swampy grounds around Hatcher’s Run where she fell.

Sallie Ann Jarrett was remembered by her comrades in the Eleventh Pennsylvania Infantry as the ultimate military dog. They noted that she tended to have a dislike for civilians but that she hated Rebels even more. When the veterans of the regiment erected a monument on the Gettysburg Battlefield in 1890 a recumbent, but ever watchful, Sallie Ann was placed at its base.

Old Drum...hunting dog

Old Drum lived the life of thousands of hunting dogs on the American frontier in the 19th century. It was not his life but his death that brought him everlasting fame.

Old Drum was well known around Johnson County, Missouri in the years following the Civil War. The black and tan hound was Charles Burden’s favorite, a tenacious tracker with a booming voice. Burden and his brother-in-law, Leonidas Hornsby, owned adjoining farms, co-existing in a more or less neighborly fashion until October 28, 1869.

Hornsby had been trying to make a go of a sheep farm but was plagued by predation from wolves and dogs. As his losses climbed to more than 100 head he vowed publicly to shoot the next dog he found on his property. When one showed up that fateful night Hornsby’s young nephew, Samuel”Dick” Ferguson, excitedly set out to dispatch the trespasser. Hornsby later claimed he ordered Dick to only shoot to scare the dog and to load the gun with corn.

The following morning Old Drum’s body was found on the banks of Big Creek. It appeared he had been dragged to his final resting spot. His side was peppered with multiple shots but no hole had completely penetrated Old Drum’s coat. Burden vowed justice for his prized hunting hound. He filed suit for damages against Hornsby, asking for the legal limit of $50.

Any evidence that Hornsby was responsible for Old Drum’s death was circumstantial and the first jury could not agree one way or the other. At the second trial Burden was awarded $25. Hornsby appealed and the original verdict was overturned, although the sheep farmer only received court costs. An enraged Burden claimed that new evidence was now available and was granted another day in court.

A fourth trial convened in September 1870 with a stunning array of Show Me State legal talent assembled to argue the demise of Old Drum. Representing Hornsby was Francis Cockrell, who would later serve 30 years in the United States Senate, and Thomas Crittenden, destined to be the 24th governor of Missouri. Speaking for Burden and Old Drum was John Philips, a future U.S. Congressman and United States District judge, and George Graham Vest, who would be a U.S. Senator for four terms.

Under oath Hornsby confessed to ordering his nephew to shoot at the dog but the defense wove a tale that it was a different dog and Drum was spotted elsewhere that night. When Vest stood up to deliver his final summation he ignored all the testimony and evidence presented in the case. Instead, he said,

Gentlemen of the jury, the best friend a man has in this world may turn against him and become his enemy. His son or daughter whom he has reared with loving care may prove ungrateful. Those who are nearest and dearest to us--those whom we trust with our happiness and good name--may become traitors in their faith. The money that a man has he may lose. It flies away from him, perhaps when he needs it most. A man’s reputation may be sacrificed in a moment of ill-considered action. The people who are prone to fall on their knees to do us honor when success is with us may be the first to throw the stone of malice when failure settles its cloud upon our heads. The one absolute, unselfish friend that man can have in this selfish world--the one that never proves ungrateful or treacherous--is his dog.

Gentlemen of the jury, a man’s dog stands by him in prosperity and poverty, in health and sickness. He will sleep on the cold ground, where the wintry winds blow, and the snow drives fiercely, if only he can be near his master’s side. He will kiss the hand that has no food to offer; he will lick the wounds and sores that come in encounter with the roughness of the world. He guards the sleep of his pauper master as if he were a prince. When all other friends desert, he remains. When riches take wings and reputation falls to pieces, he is as constant in his love as the sun in its journey through the heavens.

If fortune drives the master forth an outcast in the world, friendless and homeless, the faithful dog asks no higher privilege than that of accompanying him to guard against danger, to fight against his enemies. And when the last scene of all comes, and death takes the master in its embrace, and his body is laid away in the cold ground, no matter if all other friends pursue their way, there by his graveside will the noble dog be found, his head between his paws, his eyes sad but open in alert watchfulness, faithful and true even to death.

The case was quickly decided in Burden’s favor. He was awarded $50 and court costs. Hornsby appealed and the case went all the way to the Missouri Supreme Court before vindication for Old Drum was finalized in 1872. Vest’s speech immortalizing the loyal companion came to be known as Eulogy of the Dog. A bust of Old Drum stands in the Missouri Supreme Court and a statue, featuring Vest’s rhapsodic words, was dedicated outside the Johnson County courthouse in 1958. In 2017 the state legislature named Old Drum Missouri’s official Historic Dog.

Bob...railway dog

Most dogs make a lasting impression for their devotion and loyalty. And then there was Bob.

Bob was bred by a South Australian rancher from a German Collie Dog in 1882 to be a cattle dog. From an early age the dog seemed more interested in the workers constructing the local railroad than the cows in the field. He would run off, be brought home, run off, be brought home until when he was nine months old he disappeared for good.

The erstwhile cattle herder was rounded up with about 50 other strays and shipped to Carrieton, a railroad town with a rabbit explosion problem. When he arrived at the train station a local agent, William Ferry, took a shine to the dog and rescued him from rabbit destruction detail.

Ferry would become station master and as close to a master as Bob would ever have. Rather than hang around the station with Ferry, Bob began riding the trains. He would jump from train to train and soon became a familiar visitor across South Australia. His favorite spot to ride was atop the coal box which afforded a toasty perch. When a trip was finished Bob would just follow the engineer home for the night.

When Ferry was transferred to Western Australia in 1889 his fellow railway men hid Bob so he couldn’t take Australia’s favorite canine traveler with him. By this time Ferry realized that Bob was a free spirit, jumping on and off trains as the mood struck him. He was truly a dog of the railroad. Bob was loved everywhere he went and often his arrival in town made mention in the newspapers.

One day Bob was dognapped by a local sheep farmer. The intrigue ended quickly when Bob heard a train whistle and raced to meet the train. The crew recognized him and claimed him. When the farmer tried to protest he was told in no uncertain terms that the dog was the property of South Australian Railways and he would be prosecuted for theft if such a “mistake” were to happen again. Afterwards Bob wore a collar that was inscribed with a little doggerel, “stop me not but let me jog for I am Bob, the Drivers’ dog.” The famous collar is now on display in the National Railway Museum.

Bob the Railway Dog’s last ticket was punched in Adelaide in 1895. His praises were sung in newspapers around the British Empire. His tales on the rails would be featured in books and a widely spread narrative poem. On Main Street in Peterborough, his main base, a bronze Bob looks friendly and ready for adventure exactly as he did when he was Australia’s most famous and well-journeyed dog.

Nipper...spokesdog

Mark Barraud found a small stray terrier on the streets of Bristol, England in 1884. The little rascal seemed to have a special taste for human ankles - or so the story goes - so Barraud named him Nipper. Nipper spent his days in the Bristol theatre district where Mark worked as a scenery painter.

Unfortunately Barraud died unexpectedly in 1887 and Nipper was adopted by his 31-year old brother, Francis, who was a good enough artist to make a living as a painter in Liverpool. The two eventually moved to London with Nipper living another eight years, enjoying the ordinary life of no particular note that millions of pet dogs before him and millions since have lived. After his death in 1895 Nipper was buried in a park in Kingston upon Thames - never knowing that one day he would become the most famous dog in the world.

In 1898, working from memory, Francis Barraud started a painting of a curious Nipper looking into the horn of a new-fangled phonograph with a cocked head. Barraud called his work, finished on February 11, 1899, “Dog Watching and Listening to a Phonograph.” Like most artists he was always on the lookout for extra cash and Barraud got the idea that Edison Bell Company, whose cylinder was depicted in the oil painting might find it of value. He fired off a hopeful letter to Edison headquarters in New Jersey and received a terse response: “Dogs don’t listen to phonographs.”

There is nothing like the power of a good idea and Barraud wasn’t about to give up on this one. Surely there were more imaginative advertising targets out there. In the offices of the recently founded Gramophone Company in London he found William Barry Owen who said he would buy the painting if the artist would switch the machine to a Berliner disc gramophone. Deal. Barraud delivered the painting with a new name - “His Master’s Voice” - which became the logo for Gramophone and its affiliate in the United States, the Victor Talking Machine Company. Over the years there would eventually be 24 different versions commissioned by the company from Barraud, who died in 1924.

In 1929, the Victor Talking Machine Company was acquired by the Radio Corporation of America - RCA - and Nipper was put to work as a trademark like never before. The dog-and-gramophone logo was used around the world. From then on Nipper was everywhere selling televisions and there he was on the cover of Elvis Presley records. He showed up in Looney Tunes cartoons. Nipper statues appeared at RCA Victor buildings across the globe. The steel-and-fiberglass one on the roof of a storage facility in Albany, New York stands 28 feet tall and weighs four tons. Nipper was named one of the ten most recognizable brand logos of the 20th century.

In 1991, almost 100 years after he died, Nipper “fathered” a son. RCA launched a new ad campaign featuring a puppy named Chipper. It is a bit harder these days for Nipper to hear either “his master’s voice” or Chipper’s ad pitches as his gravesite was built over in London. But there is a brass plaque on the Lloyds Bank building on Clarence Street to remember the life of the dog that the public never knew when he was alive.

Owney...postal dog

It was no small feat to become the biggest celebrity dog of the 19th century. There was no radio, no television, no movies, no internet. You really had to put yourself out there. And Owney certainly did.

Owney’s climb up the ladder of fame began in the Albany, New York post office in 1888. He was of indistinct origins but most recognizable as a Border Terrier. He was found by a postal worker named Owen so he became “Owen’s dog.” When Owen left, Owney stayed. He seemed to have an insatiable affection for mailbags and the marvelous scents that wafted from the wondrous canvas sacks.

When his precious mailbags moved, Owney went along as their guardian. He wouldn’t let anyone touch the bags who wasn’t wearing a postal uniform. One day a mail delivery arrived with both a pouch and a pooch missing. When the driver retraced his route he discovered that a mailbag had fallen off the wagon and Owney was lying on top of it, protecting the wayward cargo.

It wasn’t long before Owney began jumping into trains loaded with mailbags. He started with local trains but soon he was leaving Albany far behind on his mail runs. Railway mail clerks were delighted to have Owney along for the ride, if not just as a good luck charm. In an era when it was not unusual to open a newspaper and read about a deadly train crash, no train Owney rode ever was in a wreck.

Once when he failed to return from a run to Montreal the Albany postal workers discovered Owney had been caged by the Canadian postmaster who was demanding $2.50 for his return to cover the cost of room and board. After that they fashioned a metal tag for his collar that read: “Owney, Post Office, Albany, New York.”

When Owney’s mail train rolled into town faraway post offices added their own tags to the collar. Owney became recognized by the jingle of tags announcing his arrival. Not all were from post offices. The celebrity dog, despite his undistinguished origins, was feted at dog shows and other events in his honor. Fore example, in 1893 the Los Angeles Kennel Club added a medal for “Best Traveled Dog” to his collection.

The tags were actually becoming a bit of a burden for Owney. Postmaster General John Wanamaker declared the little terrier the Official Mascot of the Rail Mail Service and presented him a special vest to distribute the weight across his back. There would be hundreds of tags - so many that compassionate clerks would remove them and forward them back to Albany for safekeeping.

Owney’s story was chronicled in newspapers and magazines across the country. He visited all 45 states and logged over 140,000 miles - the equivalent of traveling on his own almost six times around the globe. And in 1895 Owney did a world tour of his own, enjoying a 129-day publicity tour that took him with mailbags to Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe.

Owney made his last delivery on June 11, 1897 in Toledo, Ohio. He was older then and a bit cranky. There is no definitive account of what happened in the post office that day but it seems that a clerk tied the dog star up to wait for a newspaper photographer to arrive. Owney naturally protested and bit his captor when he tried to quiet him down. The aggrieved postal worker summoned a policeman who shot Olney. The Chicago Tribune called the incident “an execution.”

Devastated postal clerks everywhere demanded that Owney be prepared for display and his travels continued. Owney’s last stamp was finally cancelled in 1911 in Washington, D.C. at the Smithsonian Institution. His permanent home is a glass case in the National Postal Museum, which has also produced an hour-long online video celebrating his life. On display are 372 of the estimated 1,000 tags Olney accumulated in his travels. The tags are also a prominent feature of the “Owney the Postal Dog” stamp issued in 2011. Bit overdue, don’t you think?

Jean...movie actor

Helen Hayes enjoyed an acting career that spanned eight decades and earned her the nickname “First Lady of American Theatre.” In that time she never appeared with a bigger star than she did right at the beginning, when she was eight years old. “I had long curls,” Hayes remembered, “and they let me play the juvenile lead in two pictures in support of Jean, the collie. Jean was the famous dog of the day, and I was very thrilled.”

There had been dogs in films before Jean. After all, in the age of silent films a dog’s inability to talk was hardly a hindrance. British director and producer Cecil Hepworth made a star out of his collie Blair in a succession of short flickers starting with Rescued by Rover in 1905. The movie was such a massive hit in England that the negative wore out and Blair was forced to shoot his on-screen heroics twice more.

Jean was a family dog in Robbinston, Maine in the easternmost county of the United States when Blair was inventing the dog movie genre. Laurence Trimble grew up on the farm surrounded by the animals he loved. In 1907, when Laurence was 22, he struck out for New York City to make his way as a freelance writer. He took Jean, a tri-colored collie then five years old, with him.

A couple years later Trimble was working on a story about the making of movies when the nascent industry was still centered around the Big Apple. While visiting Vitagraph Studios he learned about a script that was being delayed for production because it lacked a dog who could act. Laurence volunteered that he had a dog who could fill the role and the next day he brought Jean to the set. Within minutes she was performing on cue like a veteran actor. Vitagraph signed Jean for $25 a week and Trimble was hired as a director.

Trimble would make over 100 silent films in the next 20 years with many starring Jean. Often they wnt home to film with the rugged Maine coast in the background. With such names as Jean The Match-maker, Jean Goes Foraging, and Jean Goes Fishing. Jean was branded as the “Vitagraph Dog” and every bit as popular as Florence Turner, the “Vitagraph Girl” considered the most prominent actress in the world.

Jean even laid claim to being the first reality star. When she gave birth to six puppies in 1912 the blessed occasion became fodder for a Vitagraph film called, naturally enough, Jean and Her Family.

The two mega-stars would pull a power play in 1913 when Turner, Jean and Trimble would leave Vitagraph to make movies in England. Trimble and Jean would stay three years abroad before coming home. But there would be no more movie appearances for the famous Vitagraph Dog. America’s first canine screen star died shortly after returning to the United States.

Warren Remedy...show dog

Like so many competitions the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show began with boastful talk in a bar. Seems that a group of hunters in Manhattan got to bragging on their gun dogs and decided to form a kennel club and settle their bets. The sportsmen named the new kennel after their favorite watering hole in the Westminster Hotel. The first dog show on May 8, 1877 was an immediate hit with over 1,200 dogs representing 35 breeds in competition. The New York Times reported that, “the crush was so great that the streets outside were blocked with livery carriages, and the gentlemen who served as ticket sellers could not make change fast enough.”

For the first 30 years the dogs competed only in their own groups but in 1907 the Westminster Kennel Club introduced an all-breed competition for Best in Show. Representing the Terrier Group was Warren Remedy, a smooth-coated fox terrier not yet two years old. Her owner was Winthrop Rutherfurd, whose own breeding went directly back to Peter Stuyvesant, the last Royal Dutch governor of New York in the 1600s, and John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts.

Rutherfurd started the oldest fox terrier kennel in the United States in 1880 at his sprawling estate in Allamuchy, New Jersey. The Tudor mansion was in Warren County, hence all Rutherfurd terriers carried the Warren moniker. Rutherfurd served as president of the American Fox Terrier Club and wrote the standards of the ideal characteristics of the breed. No wonder his dogs performed so well with the judges in competition.

Warren Remedy started showing in 1906 but was still considered by experts to need “a little size yet.” The next year she reached her maturity, just as the Westminster Kennel Club launched its first ever Best in Show tussle among over 2,000 dogs. Warren Remedy claimed the trophy and $50 in gold. She won again in 1908 and 1909. Some may have sniped that Warren Remedy had an unfair advantage against other dogs when her breeder wrote the standards but as Outing magazine summed up her competitive career, “at her best she was about as near perfection as a dog man ever hopes to see.”

To this day no dog has ever won Best in Show on three straight trips to Westminster like Warren Remedy. She was the most famous dog in America, appearing in magazines and shilling for Spratt’s Dog Cakes, the first manufactured dog biscuits. James Spratt, a lightning rod salesman from Cincinnati patented the Meat Fibrine Dog Cake back in 1860 and this was the first time the company had employed a celebrity endorser. When Warren Remedy died in 1912, maybe the best show dog there ever was, her passing was mourned in the New York Times.

Togo...sled dog

Brawny Malamutes were always the sled dog of choice in Alaska’s Great White North until Leonhard Seppala, a trainer and musher from Norway, helped change all that. Seppala landed in Alaska in 1900 when he was 22 years old, looking to chase gold in the Yukon. When the winter hit he found himself working as a dogsled driver. His life as a prospector was over.

A few years later the Nome Kennel Club started a long-distance race for dog sledders, following telegraph lines along the Bering Sea that linked villages and gold mining camps. The All-Alaska Sweepstakes covered 408 miles, requiring between three and four days to complete. As he built his reputation as a musher Seppala championed huskies imported from Siberia that rarely reached 50 pounds. Teams of the quick and agile Siberians came to dominate the race.

Seppala got his first sled dog team of Siberian Huskies in 1913. The dogs had been ticketed for a run to the North Pole with Norwegian arctic explorer Roald Amundsen but the expedition was called off. That same year Seppala culled his kennel of an unpromising puppy named Togo. Undersized and often unhealthy, Togo was given to a neighbor to be a pet.

Togo had other plans. He threw himself threw a window and ran back to Seppala’s kennel. When Leonhard took his teams out to train the puppy would break loose and try to keep him with his heroes. One day a team of larger Malamutes took exception to the young miscreant and administered a mauling he would not forget.

At wit’s end with Togo, Seppala put him in harness when he was just 8 months old. In his first outing Togo ran 75 miles, working his way to lead dog by journey’s end. With Togo on lead Seppala won the All-Alaska Sweepstakes a record three straight times in 1915, 1916, and 1917. World War I brought an end to the event after that.

In 1925 Nome was the largest town in northern Alaska with 1,500 inhabitants but was still isolated. When the Being Sea froze over the only way to get supplies was by train first to Nenana and the by 675 miles by dog team - a journey usually of some 25 days. That January the territorial governor received an emergency telegram from Nome that the community was threatened by a deadly diphtheria epidemic. Serum was available but would not be any good after more than six days on the trail.

Authorities organized a dog sled relay to deliver life-saving serum 675 miles to Nome. The champion musher and his now 12-year old prized lead dog were recruited to anchor the return to distressed Nome. Seppala planned to cover the entire route to meet the westward bound dog teams and return on his own. After he departed Nome additional relay teams were assembled but Togo still led Seppala’s team through by far the longest and most dangerous leg of the Serum Run - 264 miles.

The race to save Nome made headlines around the world. More than 20 drivers and over 100 dogs participated in the courageous 5 1/2 day-race over the frozen Alaskan wilderness. A curious public was eager to put a face on the heroic effort in the exotic locale. That belonged to Gunnar Kaasen and his lead dog, Balto, who had taken the last 55-mile leg into Nome. Before 1925 was out there was a statue of Balto in Central Park in New York City. The Siberian husky was there for the ceremony. He worked the vaudeville circuit for awhile, letting admiring fans see the famous dog and eventually lived out his years in celebrity in the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo in Ohio.

Balto was a sled dog in Seppala’s kennel but he had not been one of the trainer’s top 20 dogs selected for the mission. He had been pressed into duty with an auxiliary team to relieve Seppala’s crack team. Balto had never even performed as a lead dog. It was as if a star fullback bulled his way through a punishing defense for 95 yards down a football field and headed to the sidelines to take a breather on the opponents’ 5-yard line. His back-up then ran the ball into the endzone for a touchdown and wound up on all the ESPN highlight shows.

Not that an aggrieved Togo spent his days pacing his kennel. Seppala and his team were feted around the country by those in the know, making appearances in stadiums and being featured in articles and books. Seppala founded a Siberian Husky kennel in Poland Spring, Maine where Togo spent his retirement until his death at the age of 16.

The Serum Run inspired the creation of the world’s most famous sled dog race, the Iditarod, in 1973. At the headquarters of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race in Wasilla there is one Siberian husky on display to greet visitors - Togo.

Stubby...war dog

General John J. Pershing was the first American to be promoted to the rank of General of the Armies. In July 1921 Pershing met to honor one of those who served under him when he was commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front in World War I. That soldier was the General Black Jack Pershing of dogs.

The New York Times reported on the confab of historic man and historic dog: “Stubby on parade is a gorgeous spectacle. He wears a leather blanket, beautifully embroidered with the flags of the Allies in natural colors, the work of nearly a hundred French demoiselles whom Stubby met in his travels. He wears also a Victory medal, with crossbars indicating the major engagements at which he assisted. His blanket is literally covered with badges and medals which have been thrust upon him by admirers, and on the left side of his elaborate leather harness, also a gift, he wears three real gold service chevrons, while on the right side he has another gold chevron to indicate his honourable wounds.”

Stubby was always described as a brindle Bull terrier after he wandered onto a military training field in Yale University in 1917 as a stray. But he could have been almost any mishmash of breeds. Private J. Robert Conroy discovered him and named him Stubby for his short tail. He learned the bugle calls and the drills of the men of the 102nd Infantry, 26th Yankee Division and Conroy taught him a military salute, raising his right paw to his right eyebrow. That trick came in handy after Conroy smuggled Stubby aboard the SS Minnesota troop ship bound for France. When the commanding officer met the forbidden stowaway he was allowed to stay after getting a crisp doggie salute.

The canine soldier received special orders to accompany his unit to the front lines as a mascot. Stubby quickly adapted to the pounding artillery and loud rifle fire of life in the trenches. He became adept at identifying wounded allied soldiers by their voices and barked to lead medics to their positions. He correctly pegged one soldier studying a map as a German when he called to him and Stubby chased the man, causing him to fall. He continued to bark and snap at the fallen spy until American soldiers arrived.

His first battlefield injury was as a result of poisonous mustard gas. After that he was outfitted with a special gas mask and was inscrutable in detecting a gas attack, barking incessantly for soldiers to grab their masks before they were even aware of the danger. A German grenade left shrapnel in his chest and necessitated surgery and a six-week hitch in a Red Cross Recovery Hospital. As his health improved Stubby visited as many fellow wounded soldiers as he could, boosting unit morale.

By war’s end Sergeant Stubby had served in four major offensives and 17 distinct battles. Back home he marched at the head of victory parades and was a familiar visitor to the White House, dropping in on Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, and Calvin Coolidge. When Conroy attended Georgetown University Stubby went with him and was soon the school mascot. At halftime of football games he would delight the crowd by pushing a pigskin around the field with his nose. The canine war hero was given membership with the YMCA and a card that promised him “three bones a day and a place to sleep for the rest of his life.”

Stubby died in Conroy’s arms in 1926 and the honors continued to come his way after his death. His skin was preserved and he spent a lot of time at the headquarters of the Red Cross. In 1956 Conroy donated World War I’s most decorated dog to the Smithsonian Institution. He never got another dog.

Strongheart...movie actor

The journey that would land Laurence Trimble on the Hollywood Walk of Fame began with the happenstance movie stardom that came his way with his dog Jean, the Vitagraph dog. For his second canine act there would be no such serendipity involved.

With Jean’s passing Trimble set out to make another movie star dog. He had a very specific objective in his search: find a dog capable of “feelings and emotions that actual conditions did not warrant.” And he had one breed in mind, a breed not well known in the United States at the time: the German Shepherd. His study of pedigrees and performance in German police training and Red Cross service was so exhaustive Trimble narrowed his selection process down to three individual dogs. One was still in Germany in 1920 and the other two had found their way to the United States.

Trimble and his wife, screenwriter Jane Murfin, went to meet one of the immigrants, three-year old Etzel von Oerlingen, then housed in a kennel in White Plains, New York. His German breeder had feared the dog might be ill-treated in post-World War I Germany and shipped him to the United States to be sold. Upon seeing strangers in his kennel Etzel immediately commenced an attack but altered his position upon a sharp command from Trimble.

“It was this incident that made me decide this was the dog I had been seeking,” Trimble wrote later in Strongheart - The Story of a Wonder Dog. “His own actions caused his selection. He had shown that his training in the duties of a police dog had been thorough and his execution of them superb. But he was not an automat. His actions were governed by reason.”

And so Etzel - soon renamed the more marquee-friendly Strongheart - was off to Hollywood for a motion picture career. Trimble extended considerable effort just teaching the glorious Shepherd how to play and this combined with his superb military training forged the ideal canine actor. There would be stories of the old Etzel peeking through from time to time as Strongheart was known to track people of questionable integrity around the studio.

From the release of his first film, The Silent Call, in 1921 Strongheart was not simply a canine movie star but the first true dog celebrity. He traveled to personal appearances with special train accommodations. He was featured in the mainstream press and the fan magazines. He received thousands of fan letters and inspired several books. Strongheart dog food was introduced; it is still being marketed by Simmons Pet Food 100 years later.

Trimble directed Strongheart in three more outdoor adventure films in the next four years, culminating in an adaption of Jack London’s White Fang in 1925. The movie showcased the canine actor’s gifts magnificently as Strongheart, confident that he could “whip any dog that ever walked on four legs or less,” must portray White Fang in the gruesome dog fight that he loses to a bulldog he is unable to leverage to advantage.

By this time Strongheart had kickstarted the popularity of the German Shepherd breed both on and off the silver screen. There were upwards of two dozen wannabe hero Shepherds roaming the lots of Hollywood studios in the late 1920s, not all to great acclaim. The performance of Ranger in Breed of Courage was ravaged by a review in Variety: “Ranger is not a good actor…The heavy practically drags the dog towards him instead of the dog attacking, in several cases the menace falls to the floor, pulling the dog down on top to make the look of a fight.”

Some of those aspiring Shepherd actors were Strongheart’s own pups. Like many of his Hollywood brethren Strongheart found romance with a co-star, Lady Jule. The proud parents produced several litters over the years. His grandsons Lightning and Silver King both scored movie hits in the 1930s.

The year 1929 at the start of the Great Depression marked the end of both Laurene Trimble and Strongheart’s days in Hollywood. At 12 years of age Strongheart slipped on a stage set and was burned by a hot studio light. The wound turned tumorous and he died in June. Of his six Hollywood features, four have been lost entirely and the other two can not be restored to wide viewing. Later that year Trimble lost his fortune in the stock market crash. For the final 25 years of his life he devoted himself to the training of guide dogs for the blind. Trimble and Strongheart were reunited on February 8, 1960 when both received stars on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.

Rags...war dog

Usually it is the human who teaches the dog tricks. But sometimes a human can learn a few tricks from dogs. In the trenches in World War I Rags, a scruffy terrier mix, would sometimes flatten himself in the dirt without warning. His fellow soldiers soon learned that Rags could hear incoming fire before they could and when he went down, they went down.

Rags was a stray making his way on the war-ravished streets of Paris in 1918. After a bit of Bastille Day revelry in Paris a couple an American GIs stumbled over a pile of rags, which was in fact a sleeping puppy. The startled dog took no offense but instead followed Jimmy Donovan back to the base of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division.

Donovan was in the signal corps and his new companion proved to have a knack for detecting breaks in communication lines. Donovan also trained Rags to carry messages across the front lines, a particularly difficult task for a dog to master even without constant gunfire since he had to abandon one master in search of a strange new one. One critical missive delivered by Rags under fire resulted in reinforcements that broke a German stranglehold on Donovan’s unit of 42 men. The gutter puppy was a 1st Division celebrity.

In the final major campaign of the war Donovan and Rags were injured in a German gas attack. Rags lost the sight in one eye and multiple cuts to his paws. Donovan was more severely affected and eventually had to be shipped back to the states and the Fort Sheridan infirmary in Chicago. Rags, whose exploits had made him famous by now, went with him. Donovan never left the hospital and died in 1919.

Rags took up residence in the base fire house, sporting a collar tag that identified him as “1st Division Rags.” In 1920 he attached himself to the daughters of Major Raymond W. Hardenbergh who was given trusteeship of the company mascot. Rags followed the Hardenberghs to posts in New York City and Washington where he picked up more awards and more fanfare.

Jimmy Donavan had taught Rags to raise his paw high and close to his head in a version of the military salute. When Rags would make ceremonial appearances at bases he would give his salute whenever troops assembled. In more familiar canine behavior whenever Rags would move to a new base he initiated a daily tour of duty to determine the mess halls with the most pet-friendly staff and make that mess a regular stop on his daily itinerary.

Rags died in Silver Spring, Maryland in 1936 when he was around 20 years old. He was buried with full military honors. Major General Frank Parker, head of the Fightin’ First eulogized the company mascot: “Since the beginning of history animals have shared the hardships of fighting men, and Rags was an outstanding example of devotion. He was a real soldier dog.”

Rin Tin Tin...movie actor

At the first Academy Awards in 1929, honoring movies from 1927 and 1928, the ballots were counted and the Oscar for Best Actor went to……Rin Tin Tin! The chagrined organizers quickly changed the rules on the spot so that only human actors could win the coveted statuette.

It is a great dog story. But it never happened. The legend was so accepted as fact, however, that it was still being printed in biographies of Rin Tin Tin eighty years later. That it was considered plausible at all speaks to the mythmaking that surrounded the legendary German Shepherd and the clout of Hollywood dog stars in the silent film era.

The dog hero movie genre of the 1920s ascended its peak with Rin Tin Tin, or Rinty, as he was know to legions of fans. Lee Duncan, Rinty’s owner and chief spinner of tall tales, rescued two German Shepherd puppies from a bombed out French kennel in the waning days of World War I. He named the dogs Rin Tin Tin and Nenette after toy dolls French women made out of yarn to give to soldiers as good luck charms. The little female died before Duncan and Rin Tin Tin could return to his native California.

Duncan’s plan was to train his handsome new friend to perform in local shows. In doing so he naturally came in contact with movie folk who were suddenly everywhere in search of talented German Shepherds in the wake of the cinematic success of canine star Strongheart. Rin Tin Tin found work as a stunt dog on the Warner Brothers production of The Man from Hell’s River. When a dog actor balked at performing in a river scene Duncan boasted that he had a dog who could do the stunt in a single take. When Rin Tin Tin did a star was born.

Rinty was an immediate sensation and eventually starred in 26 movies. His success was credited with saving the Warner Brothers studio from bankruptcy. Maybe an exaggeration, maybe not. By all accounts though, the Shepherd with the expressive eyes was judged a phenomenal performer. As one review in the Boston Globe raved, “Rin Tin Tin enacts so many different moods that it is difficult to believe that one dog could play throughout the film. He can look like a savage wolf one minute. The next he plays with a little child and wears an almost silly smile when he does his antics.”

Rinty’s career lasted into the era of the talkies before he died in 1932 at the age of 14. Likely his passing was without drama but that did not stop the story circulating that the great canine thespian died in the mourning arms of Jean Harlow, the greatest female star of the day. Duncan arranged for Rin Tin Tin to be transported back to his native France to be interred in the Cimetière des Chiens in Paris, one of the world’s oldest pet cemeteries.

Rin Tin Tin’s death was front page news across the country. But his name scarcely faded. There were over 50 puppies, some carrying the Rin Tin Tin name as they made personal appearances and movie cameos. In the 1950s came a long-running television series, The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin. A century after his lifetime Rinty remains the definitive name in canine action adventure hero.

Hachiko...loyal dog

Like Greyfriars Bobby before him Hachikō’s devotion to family became a national symbol of loyalty - this time to the folks in Japan. The golden brown Akita’s story began on November 10, 1923 on a farm in northern Japan, his name Hachikō roughly translates to “eighth” which was his position in the litter.

The pup went to live in Tokyo with Hidesaburō Ueno, an agriculture professor at the Imperial University. Hachikō was never content to wait until Ueno returned to the house - each day he trotted to nearby Shibuya Station to greet his master upon his return from work. The routine went on every day until May 21, 1925 when the professor was not on the train. He had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died. Hidesaburō Ueno was only 52 years old.

Hachikō was given to a new home but regularly returned to Ueno’s house. When he was convinced Hidesaburō was no longer living there he went to the train station to wait. The distraught Akita would wait for nine years, looking for his friend to step off the train at the appointed time. Commuters and local shopkeepers would keep the devoted dog in treats and meatbones.

One of Ueno’s students took a special interest in Hachikō, writing articles about his vigil which made brought him national fame. According to his research there were only 30 purebred Akitas, including Hachikō, remaining in Japan. In 1934 a bronze statue was erected at Shibuya Station as the dog of honor looked on.

On March 8, 1935 Hachikō was found on the street, having died of natural causes - later determined to be terminal cancer - in the night. His statue would be melted down for the Japanese war effort in World War II but Hachikō was not to be forgotten. His fur was preserved and stuffed and would go on permanent display at the National Science Museum. There would be paintings, books and movies to tell his story. The Nippon Cultural Broadcasting company even was able to snatch a snippet of Hachikō barking on an old record and it was used in an advertising campaign in the 1990s. One of the Japanese train lines was named for Hachikō.

The son of the original artist sculpted a new statue in 1948 and it was placed in a position of prominence in front of the Shibuya Station, one of the world’s busiest. Many think it is Japan’s most famous work of public art. In 2015 the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo unveiled its own bronze statue. In this joyful rendition an ecstatic Hachikō is depicted jumping up to greet Ueno after a long day apart.

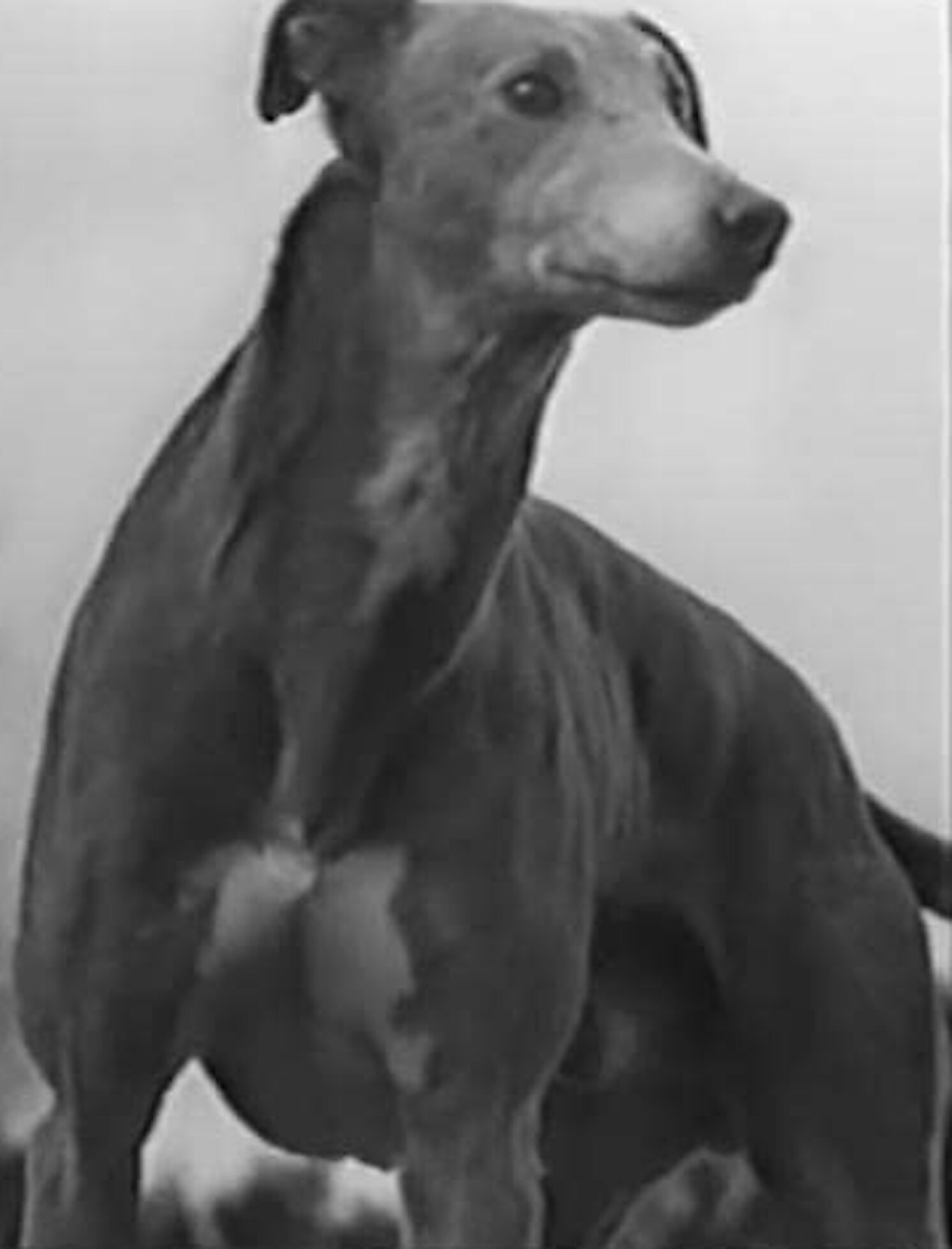

Mick the Miller...dog racer

Greyhounds are among our oldest purebred dogs, so revered by ancient Egyptians that only royalty were allowed to own them. Through the ages the greyhound maintained its position at the top of the hierarchy in the dog world, widely considered the noblest and best at hunting.

In the Middle Ages the English aristocracy began amusing themselves with coursing races, showing off the unrivaled swiftness of greyhounds in the pursuit of live rabbits. The Waterloo Cup, the grandest event of coursing began in 1836 and through the years crowds of more than 50,000 would gather to watch the greyhounds in action. Dogs like Master M’Grath (three-time champion) and Fuller (four-times a winner) were national English heroes, the results of their contests dispatched around the island by carrier pigeon.

The focus of greyhound racing shifted to the track in 1912 when Owen Patrick Smith tied a stuffed rabbit to a motorcycle in Emeryville, California. Smith said he was motivated partly by a desire to save live rabbits and partly “to make dog racing look like horse racing.” Betting on greyhounds might be good sport for the American hoi polloi sniffed British greyhound aficionados but that sort of thing wasn’t done in England.

At least not until July 27, 1926 when the Greyhound Racing Association (GRA), a private company, started artificial lure racing outside of Liverpool. By the end of the racing season attendance was averaging 11,000; the next year the GRA had expanded to 18 tracks and hosted over four million punters eager to plunge on the racing greyhounds.

A month before greyhound track racing started in Great Britain Na Boc Lei gave birth to a litter of ten puppies in the village of Killeigh, County Offaly, Ireland. The pups were the direct descendants of the great coursing champion, Master M’Grath. Although he was the youngest and smallest of the greyhound pups, the runt of the litter was targeted by odd-job man and aspiring trainer Michael Greene for special attention. During a discussion over what to name the little guy the local miller just happened to come up to the group. “Hey, it’s Mick the Miller,” someone said. The new greyhound had his name.

Greene initially planned to campaign Mick the Miller as a coursing dog, like his famous ancestor. Track racing had just started in Ireland, however, and it was decided to give Mick a try at the new game. He won his first race, the Shelbourne Sweepstakes, and a prize of £10. Mick would go on to win 15 of his first 20 races and his Irish handlers set their sights on the young sport’s biggest prize, the English Greyhound Derby, in 1929.

Mick the Miller not only won the Derby but became the first greyhound in history to cover the standard 525-yard track in under 30 seconds. He triumphed again in 1930 for back-to-back wins, a feat that would not be duplicated until the 1970s. The brindle speedster won an unprecedented 19 straight races that year. It appeared Mick had copped another Derby in 1931 in a blazing 29.89 but judges ruled that the final be re-run due to an altercation between two other dogs. A tired Mick ran a pressing fourth as 70,000 fans voiced their displeasure in London’s White City Stadium.

Greyhound racing now had not just a champion but a folk hero. Exactly what is needed to popularize a young sport. Mick the Miller became one the greatest heroes in English sports history. He wrapped up his racing career after only three years with 61 wins in 81 tries, including all the top trophies in the sport. Mick became the first dog to receive fan mail and took a star turn in Wild Boy, a comedy film about a crooked dog owner’s shenanigans to stop a rival dog from running the Greyhound Derby.

Mick the Miller spent much of his final eight years with the ladies, performing stud duties before dying in 1939 at the age of 13. The honors would continue long after his death. Royal Doulton, the 200-year old ceramics purveyor, manufactured commemorative figurines of the legendary champion. A sculpture of Mick stands on the Killeigh village green; the plinth being constructed from stone salvaged from the ruins of the Millbrook House where he was born. And Mick himself? Just two months after passing the beloved greyhound was stuffed and put on display at the British Natural History Museum in London. After a sprucing up decades later, Mick the Miller now stands in the museum’s sister gallery in Tring as he approaches the centennial of his birth.

Buddy...guide dog

Courtesy of the Tennessee State Library and Archives

Any dog can learn a command. It is the dog that can ignore that command when it would result in harm to the master, an ability known as “intelligent disobedience,” that has the stuff to be a guide dog.

Buddy and Morris Frank were born a half-world apart. Frank was a Tennessee boy who lost his right eye in a horse riding accident when he was six years old. He later went blind in his left eye while boxing with a friend. Buddy was a German Shepherd born in the Swiss Alps. It was an article published in The Saturday Evening Post on November 5, 1927 that brought them together. The article was called “The Seeing Eye.”

The writer was Dorothy Harrison Eustis, an American expat living in Switzerland where she was breeding and training her favorite dogs, German Shepherds. Her article was about dogs she saw being trained in Berlin to help German war veterans who had been blinded by poison gas in combat. Eustis wrote that the same methods could be used to assist visually impaired people in all walks of life.

The magazine was deluged with letters from people wanting to know more about the dogs, which were forwarded to Eustis. One stood out. A 20-year old Vanderbilt University student was not only willing to come to Switzerland to train but he wanted to come back to America and start an instruction center that could “give all those who want it a chance at a new life.”

A month later Morris Frank was on a ship to Europe. At the Eustis estate, Fortunate Fields, he met her two guide dogs in training, Kiss and Gala. Kiss would be his partner. It was a fine name, Morris agreed, but all the same he would call her Buddy. Frank commenced his training, connected to Buddy by a strong leather harness. After a few intense weeks they were ready to tackle their objective - to walk around the village of Vevey down the road.

One day the pair stopped into a barber shop. Buddy sat patiently while Morris got his hair cut. Then the two walked home. The freedom he experienced overwhelmed Frank. He had always been taken to the barber shop and waited to be picked up after he was done. To be able to complete an everyday, ordinary task by himself, thanks to Buddy, was what he always dreamed about.

Frank and Buddy were ready to return to the United States as evangelists for Seeing Eye dogs. They were met at the New York City waterfront by skeptical reporters and immediately put to the ultimate test - crossing a busy Manhattan street. Going from the mountain village of Vevey to the Big Apple for Buddy was like sending a Little Leaguer to bat against a New York Yankees pitcher.

As Frank would later write in his book, First Lady of the Seeing Eye, “Buddy moved forward into the ear-splitting clangor, stopped, backed up and started again. I lost all sense of direction and surrendered myself entirely to the dog. I shall never forget the next three minutes…ten-ton trucks rocketing past, cabs blowing their horns in our ears, drivers shouting at us…When we finally got to the other side and I realized what a really magnificent job she had done, I leaned over and gave Buddy a great big hug and told her what a good, good girl she was.”

Back in Nashville, Frank found that not only did Buddy unlock the streets and sidewalks of the city but her presence humanized a blind person from an object of pity. As he moved about independently he found strangers engaging freely rather than avoiding the discomfort of an interaction with someone unable to see. “With Buddy,” Frank observed, “It was the easiest and most natural thing in the world for them to say, ‘What a lovely dog you have!’”

With the financial backing of Eustis The Seeing Eye began training guide dogs in Nashville. Gala was brought over from Europe to rejoin her mate from puppyhood. Hot Tennessee summers and German Shepherds were not a marriage made in doggie heaven, however, and the operation found a new home in Morrisville, New Jersey after a couple of years. Some 14,000 dogs later the campus is still the gold standard for guide dog training.

Frank and Buddy went “on the road” advocating for new laws for people with guide dogs. Buddy was a regular on the lecture circuit; she could be counted on to bark a response to applause at her introduction. The guide dog led Frank around the White House for Presidents Coolidge and Hoover. It was estimated the pair logged 150,000 miles in support of guide dog programs.

When they first started crossing the country by train it was seldom without hassle. Frank had a friendly response at the ready: “I’m not bringing her in; she’s bringing me in!” By the time of Buddy’s death in 1938, ironically after her first airplane flight, all passenger railroads in the United States permitted guide dogs on board to remain with their owners.

Buddy was buried without ceremony under a pine tree near the entrance to The Seeing Eye school. There were already 350 graduates by then. Morris Frank would go on to have six more guide dogs, all of whom he named Buddy. There are no more Buddies being graduated from The Seeing Eye - the school retired the name of its first ever guide dog.

Patsy Ann...town dog

Patsy Ann just wasn’t cut out to be a house pet. She was an Oregon pup whose family relocated to Juneau, Alaska shortly after she was born on October 12, 1929. The English Bull Terrier was stone deaf from birth but shortly after arriving in her adopted hometown she showed an uncanny ability to detect the arrival of ships coming into port. She would trot to the dock and be there to welcome passengers disembarking in the Alaskan capital.

In 1934 the mayor anointed Patsy Ann the “Official Greeter of Juneau, Alaska.” City boosters called her the most famous canine west of the Mississippi River, more photographed than movie star Rin Tin Tin. Unofficially, Patsy Ann was “Juneau’s Guest.” During the day she made the rounds in hotel lobbies, gin joints, theaters and local shops. She would score a candy bar here, a biscuit there. But whenever she detected an approaching steamship she dropped whatever she was doing and made haste to the docks. No matter what the weather, Patsy Ann “never missed a boat.”

Most nights Patsy Ann spent in the Longshoreman’s Hall in the company of others who had salt water coursing through their veins. She passed in her sleep on March 30, 1942. The next day a large crowd turned out to watch Patsy Ann’s small coffin lowered into the icy waters of the Gastineau channel, just off the wharf where she greeted hundreds of cruise ships over the years.

The story of the Official Greeter of Juneau lived on and to mark the 50th year since her passing a bronze statue of an intense Patsy Ann looking out to sea was dedicated on the wharf. New Mexico artist Anna Burke Harris mixed clippings from dogs around the world into the casting, symbolic of dogs everywhere coming together. Hundreds of thousands of cruisers come to Juneau each year and before they disembark they are encouraged to greet Patsy Ann and touch her in the spirit of friendship.

Shep...loyal dog

Courtesy of the Overholser Historical Research Center

Shep was an unnamed sheep dog who knew no one when he arrived in Fort Benton, the oldest town in Montana, in 1936. At his funeral six years later everybody in town turned out.

The dog worked the flocks in the prairies around central Montana when his herder fell ill and was brought to St. Clare Hospital in Fort Benton. The dog trailed the wagon to the infirmary and stood vigil at the door. The herder never came out; his body was transported back East to this family. At the Great Northern Railway depot the sheepdog watched as the casket was loaded into a baggage car, emitted a mournful wail and then trotted down the tracks as the train rolled out of the station.

When the train got out of sight the dog returned to the station. He began greeting every train - four a day - that stopped at the depot. Great Northern employees took care of the dog and named him Shep. It was clear to them that Shep was a one-man dog and while he was thankful for the food and shelter his only purpose in life was finding his master.

For the next five-and-a-half years Shep met every train - an estimated 8,000. His vigil became famous and people would ride to Fort Benton to see him and take his picture. Some came with dreams of adoption. But Shep would quickly retreat to his space under the station platform after checking the incoming passengers in vain. He was featured in the “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” national newspaper column and it was said that the Great Northern Railway hired a secretary just to answer Shep’s fan mail.

Shep was already a somewhat older dog when fortune brought him to Fort Benton. Cold Montana winters did his aging joints no favors. His hearing was failing and conditions were slippery on January 12, 1942 when Shep failed to complete a leap onto the depot platform as he had done countless times before. The engineer of Old Number 235 couldn’t stop the train in time.

School was cancelled so children could join the hundreds of mourners for Shep’s funeral. Boy Scout Troop #47 carried his coffin to a burial site on a bluff above town. Great Northern employees erected a small stone obelisk next to the grave.

Over the years books and folk songs kept Shep’s story alive. Fifty years on the community of Fort Benton raised $75,000 to create a permanent memorial to their famous stray. Esteemed western sculptor Bob Scriver created a noble Shep, ears cocked, tail curled and eyes fixed down the rails expecting his master’s return. The rough granite base is purposely low so children can stand and pet Shep, forever faithful.

Skippy...movie actor

The silent film era was tailor-made for dog stardom. When no one - human or canine - could talk a dog’s expressive eyes, athletic ability, and natural charisma could carry a film narrative every bit as well as their human counterparts. Action hero dogs like Strongheart and Rin Tin Tin were every bit the stars that Douglas Fairbanks and John Gilbert were.

The sound era would require an entirely new breed of canine actor, a dog who could play a part, who could interact with humans who were exchanging dialogue. Training would have to evolve as well - handlers could no longer bark commands on a sound stage. They would have to rely on silent hand signals and dogs would have to pick up those cues while keeping eye contact with the camera. The standard-bearer for this new type of canine actor would be Skippy, a wire-haired fox terrier.

Henry and Gale East first met Skippy when he was three weeks old. The couple wasn’t looking to adopt a dog but there was something about Skippy. Millions more would shortly come to understand the same thing.

Gale East was a veteran silent screen slapstick comedienne and Henry was a prop man at MGM Studios. When Skippy was three months old Henry began training him as a canine actor. He would later be trained by brothers Frank and Rudd Weatherwax whose pioneering Studio Dog Training School would become the industry standard. No longer would Hollywood producers rely on an acceptable dog actor to show up on the set by serendipity.

Like many Hollywood stars Skippy was not an overnight success. His first film was in 1932, The Half-Naked Truth about the transformation of a carnival barker into a New York publicity dynamo. He made several uncredited appearances, mostly in background scenes before his big break came in 1934 when Skippy was cast to play the mischievous pet of high society detectives Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man.

Skippy’s portrayal of Asta made him a favorite of film-goers worldwide, as well as of crossword puzzle solvers for evermore. He practically invented the concept of scene stealing when he appeared on screen with major stars William Powell and Myrna Loy. Not that they minded all that much, even after the scamp nipped Loy one time on set. Powell tried to adopt Skippy but was rebuffed by the Easts.

The ultra-popular Thin Man spawned several sequels and Skippy - now billed as Asta - was featured prominently on the marquee. He even got his own storylines in the plot. And he was paid top dollar, earning $250 a week when the going rate for a canine actor was about $3.50 a day. Around Hollywood sound stages Skippy was considered the consummate actor. In a profile it was observed, “When Skippy has to drink water in a scene, the first time he does it he really drinks. If there are retakes and he’s had all the water he can drink, he’ll go through the scene just as enthusiastically as though his throat were parched, but he’ll fake it. If you watch closely you’ll see he’s just going through the motions of lapping and isn’t really picking up water at all.”

But Skippy was not about to be typecast. His filmography totaled 22 films, sharing takes with such Hollywood glitterati as Spencer Tracy, Bing Crosby, Jimmy Stewart, Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, and many more. Following retirement Skippy did not enjoy the same adulation as such prior canine stars as Strongheart and Rin Tin Tin, who mostly played themselves. They received fawning obituaries; he was a character actor and his final years were lost after he retired from the screen. One thing that dig not fade, however - the popularity of cheeky pet terriers, which continued to soar thanks to his character Asta.

Terry/Toto...movie actor

Two of the most celebrated Hollywood talent searches of all time took place in advance of 1939 movies. One, the hunt for the actress to play Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With The Wind was so intense it spawned its own motion picture. In the second, the search for a canine actor to play Toto, Dorothy Gale’s dog in The Wizard of Oz, was complicated by millions of fans knowing what Toto looked like from W.W. Denslow’s drawings in L. Frank Baum’s children’s book.

Carl Spitz had read the book too. Spitz trained military dogs in his native Germany and when he emigrated to America in 1926 at the age of 32 he opened the Hollywood Dog Training School. He was credited with developing the technique of using silent hand signals to direct canine actors when the movies switched from silent to sound films. Spitz found a five-year old female Cairn Terrier named Terry that resembled Toto but he was taking no chances in pursuit of one of the most coveted dog roles in Hollywood history.

Spitz studied each appearance of Toto in the beloved book and trained Terry accordingly to capture the dog’s every quirk. Terry, whose film debut was in the romantic comedy Ready for Love in 1934, won the part. She was paid $125 a week for her work on screen - more than the Munchkins were taking home. Terry wasn’t receiving hazard pay, however, which would have come in handy when one of the Wicked Witch’s soldiers stepped on her foot and necessitated a stand-in for a few weeks. While recuperating in Judy Garland’s house she charmed the child star so completely that Judy asked Spitz to adopt the terrier. The trainer politely declined.

Terry was walking the red carpet at Grauman’s Chinese Theater for the Hollywood premiere of The Wizard of Oz and the film was such a sensation that Spitz changed her name to Toto. The very recognizable terrier continued to act in movies up to her death in 1945 at the age of 11. Spitz buried her on his ranch in Los Angeles. The grave was plowed under in the 1950s to build the Ventura Freeway. In 2011 a memorial to Toto was erected in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Several years later the remains of her most famous screen companion, Judy Garland, were reinterred there as well.

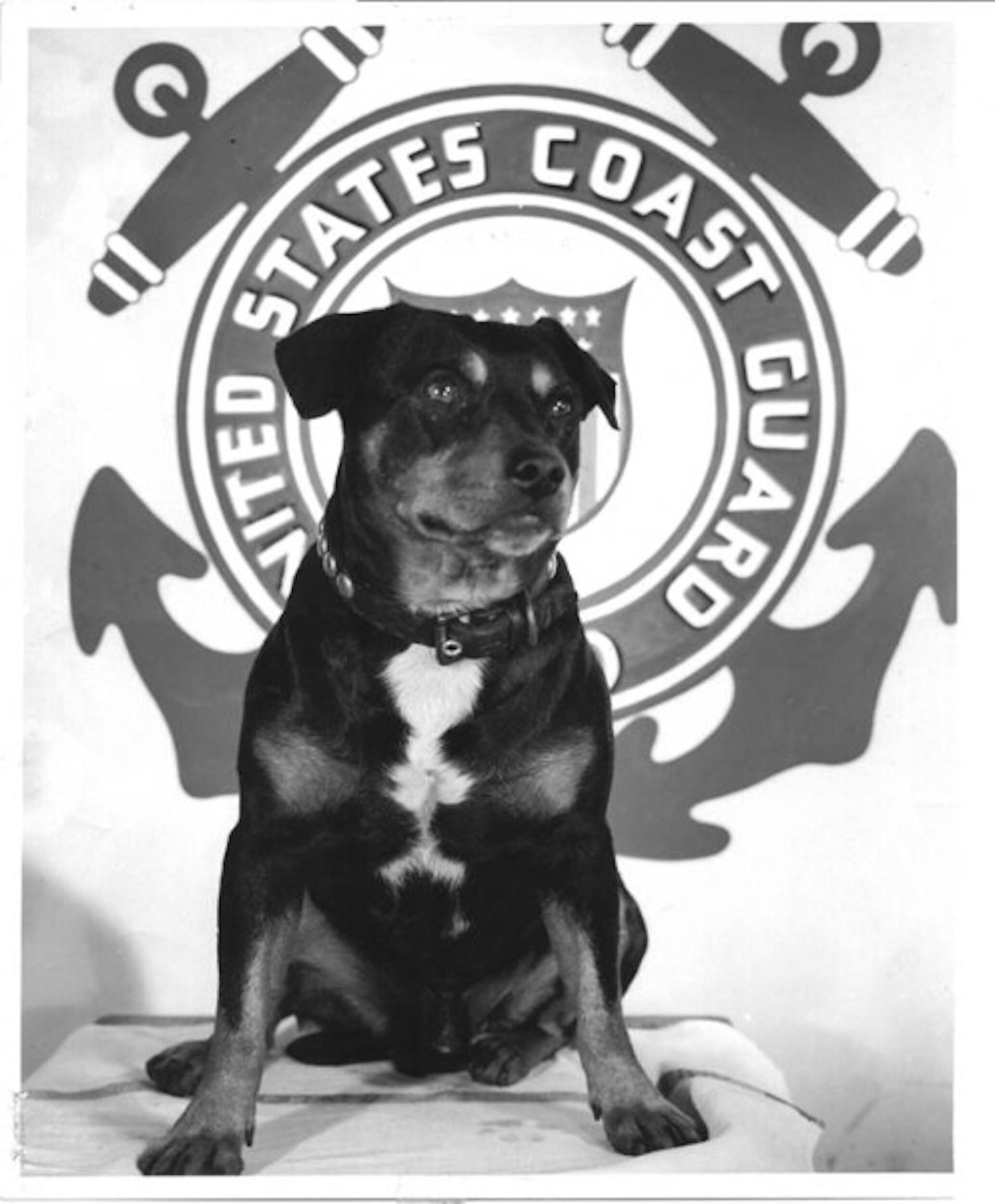

Sinbad...war dog

In 1937 Blackie Roth surprised his girlfriend with a puppy. A bigger surprise was that her landlord did not allow dogs. This was especially a problem since Roth’s home had pretty strict rules regarding dogs as well - the USCGC George W. Campbell, a Coast Guard cutter that patrolled the East Coast. Roth smuggled the little dog aboard ship and convinced the captain to let her stay. The Campbell would be Sinbad’s home for the next 11 years.

To make his enlistment official Sinbad was assigned the rank of Chief Petty Officer, the first dog officially classified. As a new non-commissioned officer Sinbad got a service record, identification numbers, and a bunk to sleep on. The mutt passed on the bunk, however, and usually slept in a hammock the crew strung up for him.

Sinbad was nothing if not a salty dog. He drank with his shipmates - boilermakers and beer straight from the tap were favorites - and was often front and center during a rowdy night of carousing. One night in New York police responded to a call of a dead dog in the gutter. They recognized Sinbad and took him back to the Campbell.

Sinbad was remembered by the editor of Coast Guard magazine as “a salty sailor, but not a good sailor. He’ll never rate gold hash marks nor good conduct medals. He’s been on report several times, and he’s raised hell in a number of ports. Perhaps that’s why Coast Guardsmen love Sinbad; he’s as bad as the worst and as good as the best of us.”

In 1940 during liberty in Greenland Sinbad disengaged from his crew for a more normal canine pursuit - chasing sheep. His good times caused several ovine deaths, almost triggering an international incident. The captain diffused the incident with a court-martial and Sinbad was found guilty of “conduct unbecoming a member of the Campbell crew.” He was stripped of his rank and busted down to Seaman Pup, forbidden to enjoy Greenland pastures ever again.

When the United States entered World War II Sinbad sailed into combat with his crew, surviving strafing attacks from enemy planes and anti-submarine warfare. After the cutter rammed German U-boat U-606 and sank it the Campbell was dead in the water. It required a tow back to Newfoundland for repairs and all but essential crew were abandoned. Sinbad was left behind as “essential” since everyone believed nothing would ever happen to the ship with their good luck charm mascot on board. And they were correct.

Sinbad’s colorful life aboard ship - and ashore - was catnip to the press and his fame spread across the country. Martin Sheridan tried to capture Sinbad for his readers and came up with “rough tough and rowdy, a combination of liberty-rum-chow hound with a bit of bulldog, Doberman pinscher and whatnot – mostly whatnot.”

Sinbad was honorably discharged from active duty with the Coast Guard on September 21, 1948. He had earned numerous service ribbons and worked his way back up in rank to Chief Dog. The old sea dog went to live out his final three years quietly in New Jersey at the Barnegat Light station. He was said to spend time at the shore looking out to sea for his old mates. And, of course, he was a regular at the only bar in town.

Brownie...town dog

One day in 1940 a dog of indeterminate origins showed up at Beach Street and Orange Avenue in Daytona Beach, Florida. There was surely some Lab in there. Some said they saw some Rhodesian Ridgeback too. If you were a stray, you could do a lot worse than this spot - the sand, the sun, happy tourists, friendly locals.

The dog mostly hung outside of the Daytona Cab Company. There were always people milling about, quick with a pet and sometimes a scrap of sandwich. And you couldn’t find a better bunch of guys than those hacks who worked for Ed Budgen.

The dog won over everyone he met with his sweet disposition. Someone said, “He was nobody’s dog but he was everybody’s dog.” Truer words were never spoken. The cabbies built the newcomer they called Brownie a doghouse out by the curb and scrawled his name across the roof.

Brownie was still learning his new territory when he was clipped by a car in the street. One of the taxi drivers witnessed the incident and hustled the injured dog to the vet. He posted a note by the taxi stand saying that Brownie had been hurt and asking if anyone wanted to help out with the hospital bill. He got $32 in the first half-hour and money continued to pour into the collection can as word spread.

Ed Budgen took the money and opened a bank account for Brownie at the Florida Bank and Trust Company. The can would remain outside the dog house and money for Brownie’s care would never run out. Some of the money was used to keep Brownie licensed and legal. He always got License #1 every year because, of course, he was The Town Dog.

Tourists helped take Brownie’s story back to their hometowns and his fame spread in newspapers and magazines across the country. Every Christmas Brownie would receive cards and care packages. It wouldn’t be right to not acknowledge the gifts so the town had Christmas cards with Brownie’s image printed up for distribution.